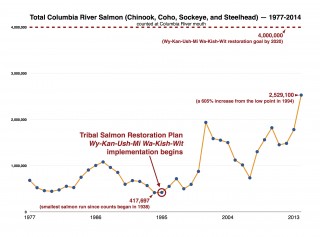

CRITFC Executive Director Paul Lumley’s Message This year’s spring chinook run was full of surprises—it came in especially early, quickly, and larger than expected. The fish counts at Lower Granite Dam, the eighth and final dam that fish must cross to get to Idaho and northeastern Oregon, especially struck me. The total spring chinook passing Lower Granite this year was 102,031 fish—the second highest run since the dam was built in 1975 and only the third time it’s ever exceeded 100,000 fish.  This is a far cry from the situation in the 1970s. During that decade, the already dwindling numbers of returning salmon began to drop even more. Each year brought news that was worse than the year before. By 1995, the fate of Snake River spring chinook seemed doomed when only 1,130 adults reached Lower Granite Dam. At one time, this many fish would return to a single stretch of river and now they represented the entire run for the hundred and hundreds of miles of the Snake, Grand Ronde, Clearwater, and Salmon Rivers and their tributaries. Rivers and streams that had once seen the return of so many fish that tribal elders spoke of practically being able to walk across the river on their backs had been reduced to just a few fish that might not even be able to find a mate. There was the very real worry that salmon were about to go extinct in several of the river systems.

This is a far cry from the situation in the 1970s. During that decade, the already dwindling numbers of returning salmon began to drop even more. Each year brought news that was worse than the year before. By 1995, the fate of Snake River spring chinook seemed doomed when only 1,130 adults reached Lower Granite Dam. At one time, this many fish would return to a single stretch of river and now they represented the entire run for the hundred and hundreds of miles of the Snake, Grand Ronde, Clearwater, and Salmon Rivers and their tributaries. Rivers and streams that had once seen the return of so many fish that tribal elders spoke of practically being able to walk across the river on their backs had been reduced to just a few fish that might not even be able to find a mate. There was the very real worry that salmon were about to go extinct in several of the river systems.

The jam of fall chinook waiting to pass Bonneville Dam during last year’s run was one for the record books and highlighted the efforts of two decades of intensive tribal restoration efforts.

This year’s spring chinook return passing Lower Granite is nearly 70 times the return of that low point twenty years ago. This turnaround didn’t happen accidentally, and the tribes played a significant role in this success. They took the threats to the sacred wy-kan-ush very seriously. Their livelihoods, diets, and very culture depended on it. In 1995, the tribes began implementing Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit, their salmon recovery plan. This plan was groundbreaking, not only because it addressed the salmon’s entire lifecycle, but also because it combined traditional tribal wisdom with cutting-edge science. The plan’s first goal was the most pressing: Halt the decline. I’m happy to report that after two decades of putting the plan into action, we have accomplished that goal. The rising returns throughout the Columbia Basin are a testament to the tribes’ wisdom, foresight, and dedication. We still have a long way to go—the next goal is to return 4 million salmon above Bonneville Dam annually—but the past few years of seeing runs larger than we’d seen in decades gives us the confirmation that tribal efforts are working. These numbers also give us the determination to keep working to ensure that salmon and tribal salmon cultures not merely survive, but thrive.