Columbia Basin Salmonids

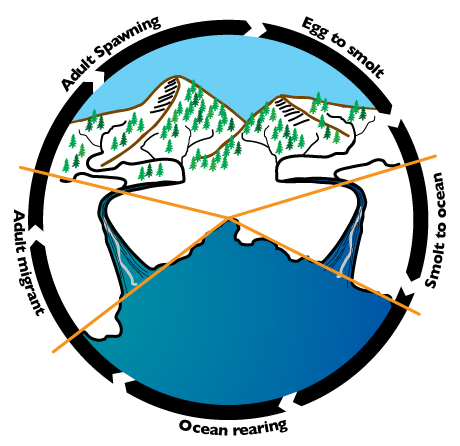

Salmon belong to a family of fish called Salmonidae. This family appeared between 30 and 50 million years ago with modern salmon appearing in the fossil record about 6 million years ago. All species of salmon are anadromous (a trait shared with the Pacific lamprey), which means adults migrate from the ocean to freshwater streams to deposit their eggs. After variable periods of rearing in freshwater, juvenile salmon migrate to the ocean to grow and mature, when the lifecycle repeats itself with the next generation. Except as noted, all salmon are semelparous, meaning that they die after spawning once.

Wild Salmon Lifecycle

After 1 to 7 years in the ocean, the adult salmon that have survived countless hazards from predators, ocean conditions, and commercial harvest return to the Columbia River and head for their home streams.

Arriving at her home stream, a female builds a nest, or redd, in fine, clean gravel.

As a female deposits her thousands of eggs, a male releases milt, fertilizing them. Both male and female salmon die soon after spawning, except steelhead and cutthroat, which may survive another year or more to spawn again.

Jeffrey Rich photo

Tiny yolk-sac fry, or alevins, hatch after 2 to 8 months. They stay in the gravel for another 1 to 3 months until the food from the yolk sac is used up. They need cold, pure water to breathe and wash away their wastes.

The fry emerge from the gravel and begin to feed on their own. Many are lost to predators, competition, or failure to adapt to stream conditions. Some types of salmon begin their migration downstream soon after emergence, while others stay in freshwater for a year or more.

During migration the fry are vulnerable to predators, such as birds or northern pikeminnow, walleye, and bass, which thrive in the reservoirs. Seven to 15 percent die passing each dam.

By the time they reach the estuary, the fry have become smolts, and their bodies are adapting to saltwater. Here they linger to feed and grow before entering the ocean. Predators, unfavorable conditions, and failure to adapt will deplete their numbers further.

Once adapted to the ocean, the smolts will spend one to seven years in the ocean, migrating thousands of miles and growing into adults before returning to their home streams to repeat the cycle.

Salmon Range

Salmon once occupied nearly 13,000 miles of Columbia River Basin streams and rivers. According to conservative estimates, the Columbia River Basin, both above and below Bonneville Dam, once produced between 10 and 16 million salmon annually. Historically, salmon runs in the Columbia River Basin consisted of 16% fall chinook, 12% spring chinook, 30% summer chinook, 11% coho, 23% sockeye, 8% steelhead, and less than 1% chum. These runs generally extended from March through October, though steelhead runs extended through the winter. Below is a video produced by Peter Galbreath and David Graves showing how the area accessible to salmon has been reduced over the 120 years between 1890 and 2011.

Like many Grandfathers before me

I spear Salmon, splashing, flapping,

These echoing waters no longer your home.

Up Celilo Falls you will dance no more.

Cleansed, Grandmother will weave

Willows into you needle-bone flesh.

Beside night fires you will roast—

Fat oozing, dripping, sizzling

My people will not go hungry.

We fast. We sing. We feast.

May your spirit always live, my friend,

If even in the Moon of High waters

From saltwater you swim upstream to die

We remember: “Return home to die.”

Salmon Lifecycle

Habitat Restoration

Spring chinook were extinct from the Walla Walla River for more than 80 years. The last run of more than a few fish was reported in 1925. Nine Mile (Reese) Dam, constructed in 1905, preceded the disappearance of spring chinook and caused the Walla Walla River to run dry each summer for nearly 100 years. Read about how Umatilla Tribes brought back chinook to the Walla Walla River.

Primary Columbia River Salmonids

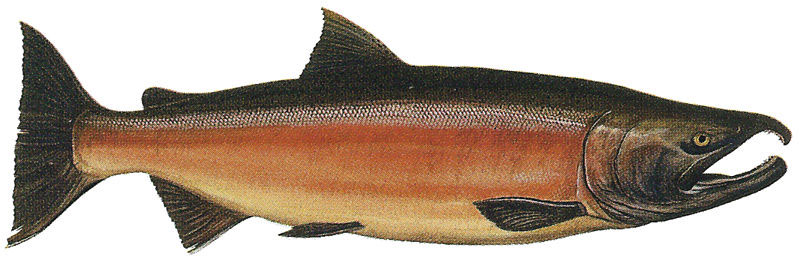

Chinook Salmon

photo courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Sometimes referred to as “king” salmon, chinook are the largest salmon species. Adult fish can grow to over four feet in length. Their typical weight is 10 – 45 lbs., with a record of 126 lbs. The chinook has a greenish back, silver sides, and a silver belly. It is covered with black spots on its back, dorsal fin, and tail. Its mouth is black. The fish darken as they mature. By the time the males are ready to spawn, they are almost black and their snouts have twisted into hooks.

Chinook salmon usually mature in their third or fourth year; however it can be as early as the second year (jacks) or as late as the eighth. Chinook return to the Columbia in the fall, spring, and summer. Some types of chinook linger in deep pools in the river until the water is just right for moving on to their spawning grounds. Chinook are known as long-distance swimmers and will travel to the farthest reaches of the Columbia to spawn.

Females can dig and deposit eggs in several gravel nests (called redds). They can release from 3,000 to 7,000 eggs. Ocean-type chinook spawn in large rivers, such as the main stem of the Columbia or Snake rivers and migrate to the ocean in their first year. Stream-type chinook spawn in tributaries and remain in the stream one or more years before migrating.

Mareas Slome with a chinook salmon at Celilo Falls. Photo courtesy Matheny Collection.

Coho Salmon

photo courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

Oncorhynchus kisutch

The coho, or “silver salmon,” has a metallic blue back and silver sides and belly. The adults turn muddy red as they begin their spawning run. Black spots are scattered along the back and upper tail. Their mouths are black except for a thin white line along their gums. Fishers have caught coho heavier than 30 lbs, but the average size is 8 lbs.

Coho adults return to the Columbia in the fall of their third year. The female may dig several redds and will deposit a total of 3,000 – 4,000 eggs.

After hatching, the young fish gather in schools in shallow areas near the stream bank. As they grow older, they disperse and become very aggressive, even towards each other. Coho typically rear for 18 months in freshwater and another 18 months in the ocean.

Coho salmon were declared extinct in Idaho in 1986, but through the efforts of the Nez Perce Tribe, they were successfully reintroduced and now return in numbers that support a fishery in a number of rivers and streams in the state.

Restoration Success

Coho salmon were officially declared extirpated, or non-existent, in 1985 in the Clearwater and other Snake River subbasins in Idaho. This was unacceptable to the Nez Perce Tribe. Understanding the cultural and ecological significance of coho to the Clearwater River, the Nez Perce Tribe worked hard and has been successful in bringing these fish back. Read about this project.

Sockeye Salmon

photo courtesy US Fish & Wildlife

Oncorhynchus nerka

Immature sockeye salmon have silvery sides and bellies and greenish-blue backs. As they mature, they turn bright red. The males’ heads become olive-green. The upper jaw and snout turns black. The lower jaw turns light gray. Most Columbia River sockeye adults are 6-8 lbs.

Most sockeye return from the ocean as four-year-olds, but some return as young as three or as old as eight. All require a lake at the headwaters of their chosen stream in which to rear. The adults pass through the lake to smaller, tributary streams where the females dig their redds. The female releases an average of 3,500 eggs. After hatching in early spring, the young fish move immediately into the lake. Most will spend a full year there before migrating to the ocean.

Perhaps the most famous lake where sockeye return is Redfish Lake in Idaho. The lake got its name from the red color of the returning sockeye salmon. To get to the lake, sockeye swim a journey of 897 miles and climb over 6,500 feet in elevation.

Though I have never performed the feat of walking across a stream on the backs of fish, which many an old timer will swear he has done, I have certainly seen fish so numerous near their spawning grounds that nowhere could you have thrown a stone into the water without hitting a salmon.

Steelhead

photo courtesy US National Park Service

Oncorhynchus mykiss

Steelhead salmon are ocean-going rainbow trout. They are a solid gray until their skin darkens at spawning time. Occasionally, a reddish streak shows up on their sides.

Steelhead migrate to the sea throughout the year. Some migrate after their first year, but most wait until after two years. As the young go downstream, they pass adults moving upstream to spawn. Most steelhead return after two years at sea. More return in the summer than in the winter.

Winter fish spawn within one or two months. Summer fish may wait as long as six months. The female digs a huge redd, covering an area of up to 60 sq. ft. She will bury the eggs in up to a foot of gravel. The female will release from 200 to 9,000 eggs depending on her size and type of stock.

Unlike other salmon species, about 10 to 15 percent of steelhead don’t die after spawning. These steelhead that survive after spawning are called “kelts.” They can swim back to sea and return to spawn again.

A Second Time Around

Unlike the other salmonids in the Columbia Basin, some steelhead can survive spawning. These “kelts” return to the ocean to repeat the process again. Yakama Nation and CRITFC scientists partnered on a project to explore how innovative strategies could improve the successful repeat spawning of steelhead kelts in the Yakima River.