Climate Change

A threat to ecosystems and the cultures based on them.

Low reservoir level in Northern California. Photo courtesy California State University, Sacramento.

While climate change affects all the First Foods, CRITFC’s work obviously focuses on how it will affect fish and the watersheds in which they live. And to be frank, the picture is not very good. For a species dependent upon cold, fast moving water, the changes that climate change brings will be a disaster. As the region warms, winter snows instead fall as rain and what snow does fall melts earlier. This results in the water traveling through the system during the winter, leaving much less during the hot summer months. The increased winter flows scour the riverbeds, disturb nests, and cause physical damage to both salmon eggs and juveniles, while the lower summer flows increase water temperatures further and reduces the overall habitat available to salmon. In the winter, salmon eggs are hatching too early, and in the summer, stream flow and salmon migration patterns are shifting earlier and earlier. The warmer summers will place an increased demand on the hydrosystem to power more air conditioning, which would mean decreased spill to aid salmon smolt migration and higher stress on returning adults. These effects are compounded by ocean acidification due to increased carbon emissions in the atmosphere. The years of collaboration, hard work, and millions of dollars spent on restoring salmon populations could all be undone by an ecosystem rendered inhospitable by climate change.

Everything is Connected

Our cultures and histories are intertwined with the First Foods, and we harbor considerable knowledge about the best approaches to sustainable preservation and replenishment of these foods. The tribes are working to prepare for the coming changes, including helping salmon in an altered climate with habitat projects designed to help cool down tributaries and exploring alternative hydrosystem operations. These efforts, however, won’t stop a warmer climate. That will require dedicated international cooperation. The tribes have also taken on a role in advocating for the United States to address this issue on a national and international scale. One of the most precious traditional teachings is the concept that “everything is connected.” For thousands of years, the tribes lived in an appropriate and sustainable way on the earth. To properly address this threat, the world must be willing to listen and incorporate the traditional wisdom of the tribes into their activities and actions.

We must begin preparations to maintain our community and our natural resources. We must carry forward our culture and traditions for our tribes’ future and for your own families’ well-being.

For many generations, you will be challenged with a changing climate. But always remember, since time immemorial, we have looked to our elders for their wisdom and guidance, and within our children we will always see hope.

Climate Research and Resources

Click here for a collection of scientific resources, research, and data sets pertinent to climate change in the Columbia Basin.

A team of more than 300 federal and non-federal experts—including individuals from federal, state, and local governments, tribes and Indigenous communities, national laboratories, universities, and the private sector—volunteered their time to produce the assessment, with input from external stakeholders at each stage of the process. A series of regional engagement workshops reached more than 1,000 individuals in over 40 cities, while listening sessions, webinars, and public comment periods provided valuable input to the authors. Participants included decision-makers from the public and private sectors, resource and environmental managers, scientists, educators, representatives from businesses and nongovernmental organizations, and the interested public.

The two chapters particularly pertinent to the interests and priorities of the CRITFC member tribes are:

photo: Facing Climate Change Project

Tribal Climate Change Strategies and Efforts

The survey information indicates that the observations of climatic changes by tribal members are increasing. Many are surprised at the extent and high rate of change, occurring within their lifetimes. They are concerned that climate change will result in significant adverse impacts to tribal food security, cultural continuity, sovereignty, economic opportunities, ecosystem balance, human health, and environmental justice. Additionally, they are very concerned that climate change is compounding the adverse effects of other ecosystem stressors including dams, increased land development for urban, agriculture, forestry, and other uses, and associated pollution.

The interviewees expected that climate change impacts would occur faster than the rate at which the tribes can adapt. However, they were hopeful that the tribes would adapt “no matter what,” because they have to. They do recognize that adaptation will require changes in management of their natural resources and cultural expression, and in working together more effectively.

Tribal and CRITFC staff are addressing the effects of climate change on fisheries and water resources, as well as other natural and cultural resources, by developing mitigation and adaptation tools for the tribes to implement on a local, regional and national level for the next seven generations. Member tribes are also participating on regional and national scientific forums and working on implementing policies and strategies to address climate change impacts.

During the past fifty years, the Columba Basin tribes have made incredible strides in the federal courts toward protection of environmental and cultural resources. There are more and more opportunities for the tribes to participate and integrate traditional knowledge in regional forums addressing climate change issues with the state, federal and local agencies and to make tribal concerns a major focus based on these precedents.

Tribal Adaptation Plans

The effects and magnitude of climate change is affected by a variety of conditions, including elevation, topography, forest coverage, and other environmental or ecosystem variables. To properly formulate strategies to address these changes, several of the CRITFC member tribes have published plans specific to their region.

Yakama Nation

Published in 2019 and adopted in 2021, the Yakama Nation’s Climate Adaptation Plan for the Territories of the Yakama Nation states: This document is an acknowledgment that climate change is real and that it poses a threat to our grandchildren, our culture, and our way of living. This document represents the first collective effort by our many governmental departments and programs to identify (1) important resources and cultural components most likely to be impacted by climate change, (2) work we are currently undertaking that recognizes and will help to reduce climate change impacts, and (3) specific recommendations for deeper analyses of vulnerabilities and risks to our most important interests and adaptation actions that we should implement now.

Published in 2019 and adopted in 2021, the Yakama Nation’s Climate Adaptation Plan for the Territories of the Yakama Nation states: This document is an acknowledgment that climate change is real and that it poses a threat to our grandchildren, our culture, and our way of living. This document represents the first collective effort by our many governmental departments and programs to identify (1) important resources and cultural components most likely to be impacted by climate change, (2) work we are currently undertaking that recognizes and will help to reduce climate change impacts, and (3) specific recommendations for deeper analyses of vulnerabilities and risks to our most important interests and adaptation actions that we should implement now.

The plan’s goal is to be a starting point for the conversation about climate change and planning for adaptation throughout all of the territories of the Yakama Nation. It is derived from the experience of the Yakama Nation people, its tribal programs, and findings from regional experts on these important topics. “This document is one way we can educate ourselves about current vulnerabilities and future risks and share ideas about actions that we may need to take to build climate resilience. It is a living document that will be revisited and adjusted over time to reflect new information, new understandings, and new priorities.”

Download the Climate Adaptation Plan for the Territories of the Yakama Nation.

Nez Perce Tribe

To address climate change induced risks to their homeland, in 2011 the Nez Perce Tribe’s Water Resources Division worked with the Model Forest Policy Program to formulate a climate change adaptation plan for the Clearwater River Subbasin. The intention was to better understand the projected local impacts of climate change and to identify some key adaptation strategies to best preserve the natural resources of the Clearwater River subbasin. The plan is the result of a year of community team effort, deep and broad information gathering, critical analysis, and thoughtful planning. It addresses local climate risks, fits local conditions and culture, and takes advantage of identified opportunities. The main emphasis of the climate change adaptation plan was on forest and water resources and the potential economic impacts of climate change on those resources. This climate change adaptation plan aims to begin the process of adapting to those climate impacts that cannot be avoided by developing strategies to protect forest and water resources and ensure the economic stability of the region.

To address climate change induced risks to their homeland, in 2011 the Nez Perce Tribe’s Water Resources Division worked with the Model Forest Policy Program to formulate a climate change adaptation plan for the Clearwater River Subbasin. The intention was to better understand the projected local impacts of climate change and to identify some key adaptation strategies to best preserve the natural resources of the Clearwater River subbasin. The plan is the result of a year of community team effort, deep and broad information gathering, critical analysis, and thoughtful planning. It addresses local climate risks, fits local conditions and culture, and takes advantage of identified opportunities. The main emphasis of the climate change adaptation plan was on forest and water resources and the potential economic impacts of climate change on those resources. This climate change adaptation plan aims to begin the process of adapting to those climate impacts that cannot be avoided by developing strategies to protect forest and water resources and ensure the economic stability of the region.

Download the Nez Perce Clearwater River Subbasin Climate Change Adaptation Plan.

Nez Perce Tribe Climate Change Coordinator Stefanie Krantz has prepared a climate change overview and its potential impacts to Columbia River basin tribes: Climate Change What Can We Do? Presentation

Additional Research and Resources

Click here for a collection of other scientific resources, research, and data sets pertinent to climate change in the Columbia River basin.

Analysis of Columbia Basin Water and Fish Resources

The issue has been released as a stand-alone hardback book. Click here for ordering information.

photo: NASA

Climate Change Challenges for Columbia Basin Fish

Mainstem Rivers (Columbia and Snake Rivers)

Threats or issues

- Higher summer water temperatures in reservoirs will stress both juvenile and adult fish, affecting their migration timing and survival, and may benefit non-native predatory fish.

- Lower summer flows will increase competition for limited water supplies in tributaries and mainstem rivers for different uses (hydropower, irrigation, fish migration).

Actions that could help address these issues:

- Manage the Columbia and Snake Rivers hydropower system to a greater extent to assist salmon migration and survival.

- Support tribal participation in the Columbia River Treaty (CRT) renegotiation with Canada to ensure that future scenario planning includes consideration of climate change and ecological concerns are included in the next CRT.

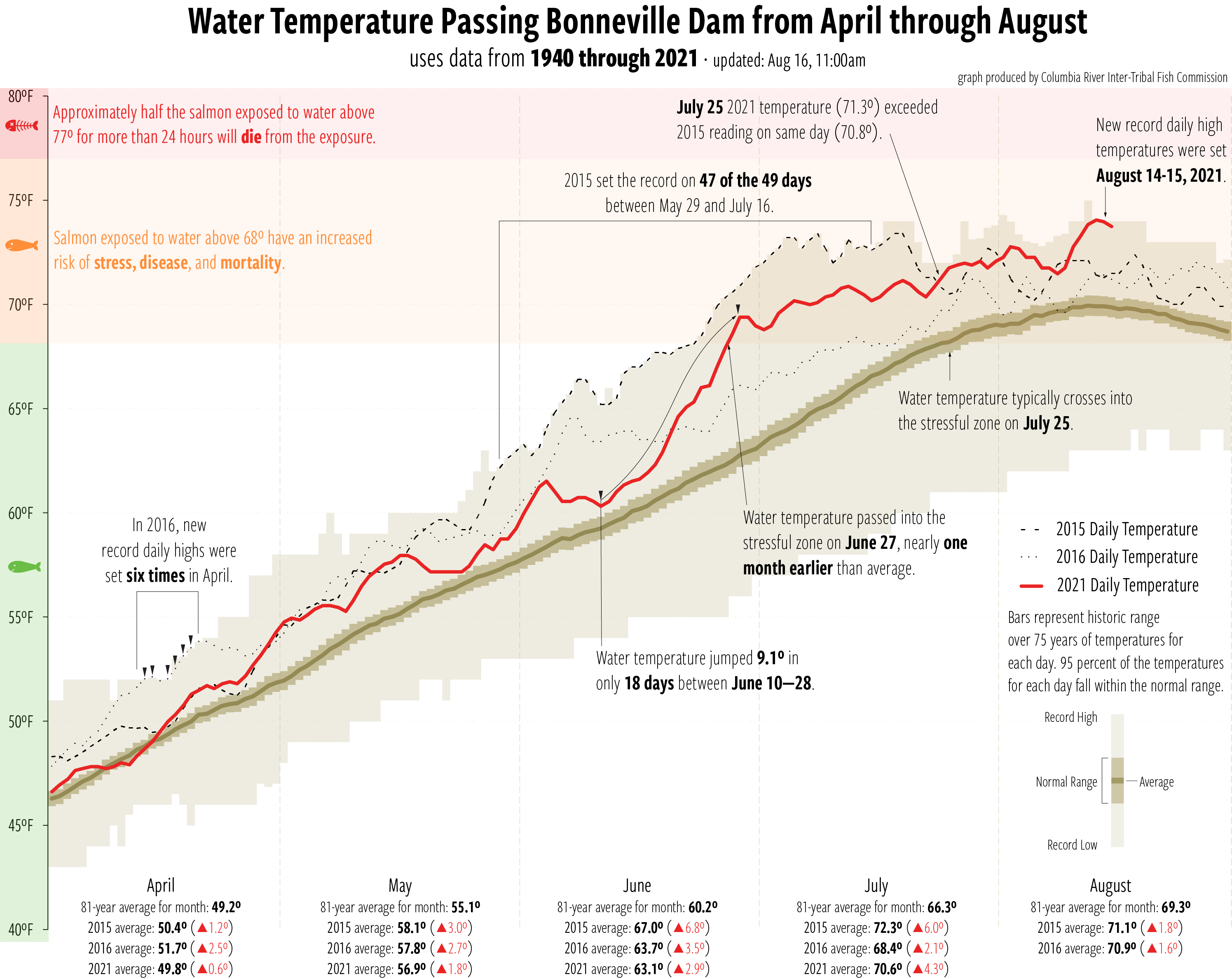

Click graph to enlarge.

2015 saw some of the longest stretches of warmer that average water temperature at Bonneville Dam, setting a daily high temperature record nearly 50 times over the summer. During the late spring of 2016, river temperatures followed a similar trajectory in terms of above-normal water temperatures, however favorable weather conditions brought conditions down from record highs later in the season.

Watershed Health

Threats or Issues

- Higher summer water temperatures in the tributary watersheds will stress both juvenile and adult fish (All fish life stages have optimum temperature ranges. Warmer temperatures increase juvenile metabolic rates and can impede or kill adults during their upstream migration).

- Lower summer stream flows will change channel structure, impede upstream migration of adult fish and contribute to water temperature increases.

- Higher peak winter flows will likely cause erosion of sediment that can damage salmon/steelhead spawning areas, scour eggs, and “wash out” the emerging fry of fall-spawning populations.

- Earlier spring runoff will alter the migration timing of smolts in snowmelt-dominated systems. Migration patterns have naturally evolved to move juveniles to the ocean at the same time that ocean upwelling delivers important food sources.

- Fish populations at the greatest risk of extinction will likely be those already in habitats that are near the limits of their thermal tolerance, and for those with less resilience and diversity.

Actions that could help address these issues:

- Protect and restore stream connectivity to coldwater refugia (including connections to side channels and the river floodplain).

- Restore ecosystem function to streams and rivers (including riparian restoration, livestock management and other restoration actions).

- Explore means for greater flexibility in the application of water rights and their potential use for ecosystem functions.

- For populations that are most vulnerable, further genetic research into ways of increasing resiliency to climate change is warranted.

- Reduce existing stressors on fish, including fish toxins, habitat degradation, and impediments to fish migration.

Ocean and Estuaries

Sardines swimming in a Pacific Ocean kelp forest. Photo courtesy California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Threats and Issues

- Changing ocean conditions (higher water temperature and ocean acidification) will alter the marine food web and will affect salmon/steelhead

- Sea level rise will likely reduce coastal estuarine habitats used by juvenile salmon.

Actions that could help address these issues:

- Support research into how climate change may affect marine food webs that are critical to salmon and steelhead.

- Protect coastal estuarine habitats that are used by salmon and steelhead.

Prioritization of Habitat and Restored Fish Passage

Grand Coulee Dam.

The best cool water habitats for fish populations in the Columbia Basin are in the upper watersheds of central Idaho and the Upper Columbia, in areas that are impeded by large dams. Restored passage to these areas should be included as an important climate change strategy to protect CRB populations, and to ensure the overall survival of these species into perpetuity.

The Wallowa Mountains, July 2015. That year, more winter precipitation fell as rain, there were drought conditions during the spring, and the area experienced unusually high summer temperatures. By July the mountains were snow-free. For comparison, below is a photo of the mountains in July 2012. (Click images to expand.)

photo: Joseph Canyon, Oregon, by Marc Shandro.

Seven Generations

Global climate change is a direct threat not only to ecosystems but the human cultures built on them. Climate change will affect everyone, but the tribes will feel a particular sting, as the very foundation of our cultures is based on respect for and wise use of the natural resources the Creator has given us. While we seek ways to influence national and international responses to reverse climate change, as individuals and communities, our task will be to try to understand what to expect in an altered environment and how to prepare for it in a way that perpetuates our culture.

The Walla Walla word supaneeqxmeans “the action of turning something around to look at it from all sides.” It is used not only to turn around an object, but also an idea, problem, or threat. It was born out of the realization that everything is multifaceted and only a broad understanding can lead to an appropriate preparation and response.Supaneeqx was the method by which the tribes evaluated problems within their families, their villages, their tribes, and between tribes. Today, the idea meets its greatest challenge and its greatest scope, not only for the tribes, but for the entire planet: to create an appropriate response to the threat of global climate change. Knowing that the fate of future generations depends on all our actions, it is humanity’s challenge to see all sides of this issue, understand all points of view, anticipate the consequences of our decisions, and make preparations for the road that lies ahead.

A fundamental teaching from the native peoples of this continent was to make decisions with the seventh generation in mind. Another was that it is humanity’s duty to be the voice for the earth and everything on it. Climate change happened because people didn’t abide by these two teachings. The native peoples of the Americas have taught the world many things, but it is imperative that it learns these two teachings in order to stop harming the earth and its climate and to provide the will to carry out the difficult task of undoing the damage that has already been caused.