Portland, Oregon – Hatcheries are an effective tool for rebuilding abundance and productivity of chinook salmon without impacting wild fish according to research published today in the journal Molecular Ecology(1). Through a study of the Nez Perce Tribe’s Johnson Creek Artificial Propagation Enhancement (JCAPE) Project, researchers found hatchery-reared salmon that spawned with wild salmon had the same reproductive success as salmon left to spawn in the wild. The study focused on a population of chinook salmon whose natal steam is located in central Idaho, almost 700 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean.

The JCAPE study results refute a commonly held misconception and some previous research that suggests interbreeding of hatchery-reared fish with wild fish will always decrease productivity and fitness of the wild populations.

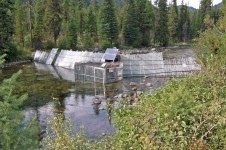

A weir across Johnson Creek allows tribal biologists to collect wild fish for broodstock while remaining fish are passed upstream to spawn.

“The Johnson Creek research clearly demonstrates how supplementation programs can boost populations and minimize impacts to wild fish populations,” said Dave Johnson, Nez Perce Tribe Fisheries Program Manager. “There will always be a need for hatcheries as long as dams exist on the Columbia River. The goal should be wiser use of the hatchery tool.”

The study used DNA from all returning adults collected over a 13-year period to track parents and their offspring and to determine how successful hatchery fish were at mating in the wild when compared to wild fish. The study showed a clear boost to the number of adult salmon returning to the population from supplementation, where fish taken in to the hatchery produced an average of nearly 5 times the number of returning adults compared to the fish that were left in the wild to spawn. A key finding of the JCAPE study was that hatchery-origin fish that spawned naturally with a wild fish had equivalent reproductive success as two wild fish, suggesting that chinook salmon reared for a single generation in this supplementation hatchery did not reduce the fitness of wild fish. Similarly, productivity of two hatchery fish spawning naturally was not significantly lower than for two wild fish.

“Our results question the generalization that all hatchery fish negatively impact the fitness of wild populations,” said Maureen Hess, geneticist with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and lead author on the study.

The Nez Perce Tribe began the Johnson Creek Artificial Propagation Enhancement Project in 1998 after tribal biologists observed critically low numbers of returning adults to Johnson Creek, a tributary to the South Fork of the Salmon River. By 1995, the number of spawning fish pairs in Johnson Creek had been reduced to five. Adult return numbers are now consistently meeting the JCAPE Project short-term abundance goal of 350 returning adults, with the project already returning more than 1,000 adults in some years.

“Supplementation is a tool that must be employed if we are going to maintain and rebuild declining salmon populations,” said Silas Whitman, chairman of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee. “The Johnson Creek study is just one example out of several supplementation programs that play a significant role in recovering Columbia Basin salmon runs. The Pacific salmon management world should consider supplementation as a recovery tool if the region is going to realize healthy and sustainable salmon returns.”

Salmon populations in the Columbia Basin continue to face problems of loss and degradation of freshwater habitat, and significant juvenile out-migration mortality associated with the hydrosystem. The tribes have argued that supplementation programs that incorporate wild fish as broodstock into their hatchery programs and place fish back in to their natural spawning areas are important to recovery.

“The public and the Pacific Northwest want abundant salmon runs. We all deserve abundance,” said N. Kathryn “Kat” Brigham, chairwoman of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. “The tribes have always supported using the best available science to inform good management decisions. This study documents what we have believed all along – that hatcheries are needed to rebuild natural salmon populations. Our goal is to use hatcheries as wild salmon nurseries to protect our treaty fishing rights in all of our usual and accustomed areas and to rebuild salmon runs. We hope that the co-managers and the science groups will use the Johnson Creek study results because it sets a new benchmark to guide the management of hatcheries.”

(1) Hess et. al., 2012. Supportive breeding boosts natural population abundance with minimal negative impacts on fitness of a wild population of Chinook salmon. Molecular Ecology. DOI:10.1111/mec.12046

The article is available on-line at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mec.12046/abstract