This article and its accompanying photos are the final project for CRITFC’s 2017 social media intern Cyrus Lyday. CRITFC hosted Cyrus through the Siletz Tribe’s tribal internship program.

Johnny Jackson, a hereditary river chief of the Yakama Nation tells a story about wild steelhead returning to the rivers in his youth. He said that many years ago steelhead used to be in such abundance that fishers could spear them out of rivers. Where there was flowing water, there were steelhead. The Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, and Warm Springs, all member tribes of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, envisions a future where this is possible.

This spawning season, CRITFC and its member tribes will bolster the population of B-index Steelhead at Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River by an estimated 20%. This increase is thanks to CRITFC’s Steelhead Kelt Reconditioning program.

“Kelt” is the life stage of steelhead after they spawn. Steelhead’s latent ability to make the physically demanding trip from river to ocean multiple times differentiates them from salmon and qualifies them as an iteroparous fish. This is in stark contrast to other Columbia river basin salmon, which are semelparous, dying shortly after spawning.

Iteroparity is the key to the Steelhead Kelt Reconditioning program, which began in 1999. CRITFC began to record many kelts at different monitoring sites at dams throughout the Columbia. The ferocity of the journey through the hydrosystem to sea and back made kelts mostly unable to complete a second attempt at reproduction, despite having the capacity to.

CRITFC works in partnership with the Yakama Nation in the Yakima River, and the Nez Perce Tribe in the Snake River to implement its Steelhead Kelt Reconditioning project. The tribes handle the fish collection and feeding, and CRITFC collaborates with them to design and conduct experiments.

Navigating a system not designed for them

“It’s really hard for small fish to get through the hydrosystem,” said Doug Hatch, Senior Fishery Scientist and head of the Steelhead Kelt Reconditioning program, “it’s almost impossible for large fish to get through the hydrosystem going downstream.”

“The hydrosystem bypasses are designed for smolts,” Hatch explains, “adult fish have some difficulty in the bypasses, and even when we see decent survival to the lower Columbia River the resulting abundance of repeat spawners has been low.”

“We started seeing a large number of kelts at different screening locations and we thought, ‘what if we were to do some kind of intervention on that life stage and use that as a restoration strategy?’” said Hatch. “So we started collecting them at Prosser Dam on the Yakima River.”

Prosser Dam, in eastern Washington between Kennewick and Yakima, served two purposes to the program. It screened fish, allowing kelts to be identified and captured, and the hatchery adjacent to the dam served as a holding and culturing facility.

“This thing started as, ‘can you collect these fish and come up with ways to keep them alive and then maybe remature?’” said Hatch. “We were able to do that. Then, it was evaluate all the ways of: is it valuable, is it useful, what’s the benefit?”

18 years later the benefits are clear

Wild kelts are being reconditioned at different places along the Columbia River, and are being released in the Yakima, Methow and Snake rivers. In fall 2016, about 280 kelts were released in the Yakima River, making up about 15% of the spawning population. This year CRITFC is projected to release around 100 kelts at Lower Granite Dam in the Snake River, making up 20% of the spawning population.

Kelts are 90% female, which are more valuable to the spawning process. When steelhead returns are low, as they are this year, the kelt program can provide a real boost to available spawners.

“If we only get 1,100 at Bonneville, and we catch a couple hundred of them, and there is some survival loss, we might be talking about a run of Wild-B fish at Lower Granite that might be down at 800, less maybe. If our kelt program can actually be successful this year in adding another 100 natural-origin B-steelhead and sending them off to spawn, you’re increasing the spawning population by 20%. So that’s a big deal,” said CRITFC Fishery Scientist Stuart Ellis.

Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River is the most important research facility in terms of steelhead spawning. “Historically we’ve mostly used counts at Lower Granite to be an index of our total escapement… In general we track our overall wild fish in the Snake by estimating abundance at Lower Granite,” said Ellis. Most steelhead spawn in areas of the Snake River that are snowed in throughout the duration of spawning season, creating the necessity to count at Lower Granite.

“We are experiencing a low run of not only B-index steelhead but the total run of steelhead,” said Ellis. “We’ve had a pretty good abundance of fish overall in the past 10 years, and steelhead runs have been quite a bit higher, but they’re kind of cycling downwards.”

B-index, or B-run, steelhead are classified as such due to their size; if a steelhead measures over 78 cm (30 in) it is classified as a B-index fish, while anything under 78 cm is an A-index fish. Most B-run fish return to Idaho, primarily to the Clearwater river basin.

The impacts of climate change

Biologists anticipate a low 2017 steelhead return due primarily to a two climate-related factors.

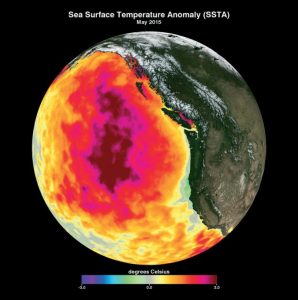

“We think that the most likely causes for those low steelhead returns this year are poor out-migration in 2015,” said Ellis. “We had really low, warm water that we think the smolts didn’t survive going out to the ocean. When they got to the ocean, we suspect that they migrated out into the Gulf of Alaska – into this patch of warm water that, at that time, was being commonly called in the news ‘The Blob’.”

‘The Blob’ was a large mass of unprecedented warm water in the Pacific Ocean, specifically the Gulf of Alaska. This mass of warm water created harsh living conditions for steelhead in 2015. (read about The Blob here: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/02/space-map-pacific-blob/)

Steelhead were more adversely affected than their salmon counterparts due to their path of migration. It is theorized that steelhead migrate West and North into the pacific ocean, but it is unclear where exactly in the ocean most steelhead travel during their time there. Salmon experienced some warm water in the ocean that year, but were able to find refuge from The Blob by following their usual migration route up the coast.

Regardless of poor conditions, it is still too early to tell if the run will complete with poor numbers. “There are some challenges in taking these broad groups of fish and just making pronouncements on how things are going to be,” said Ellis. “You can kind of look at these past patterns and make educated guesses out of them, which we do, but there is a lot of variability in this, so we really don’t know for sure what the state of things is going to be… We don’t have specific fishery issues today, because it’s too early.”

CRITFC is currently working to add capacity to the Steelhead Kelt Reconditioning project. One of the current goals is to build a new facility in which to recondition more fish.

“There is no other program that will have the impact to wild adult fish that the kelt program has,” said Hatch.